Optimised techniques for arboreal activities In 2018 Fund4Trees, the Arboricultural Association, Tree Fund and Teufelberger announced funding for a project intending to map the body’s movements during tree climbing, utilising and comparing different techniques to analyse the pressure on both joints and muscles. The aim of the research, led by Alexander Laver of Tree Logic, […]

Optimised techniques for arboreal activities

In 2018 Fund4Trees, the Arboricultural Association, Tree Fund and Teufelberger announced funding for a project intending to map the body’s movements during tree climbing, utilising and comparing different techniques to analyse the pressure on both joints and muscles. The aim of the research, led by Alexander Laver of Tree Logic, is to gain a better understanding of how we use our bodies in the tree and how potential injuries are sustained, including the mechanisms for longer-term injuries. In this article Alex provides a detailed update on the research.

Climber’s movements being captured live (right). The image on the left shows how the software can highlight which muscles are being loaded in a particular work position.

Recent advances in biomechanical motion analysis equipment have enabled the measurement of three-dimensional human movement within environments that were previously inaccessible.

Earlier motion analysis was performed using optical tracking equipment which, whilst accurate, was unsuitable for use outside and this excluded its application to tree climbing. However, motion-capture equipment is now available which uses inertial tracking sensors and can operate in more realistic scenarios such as within the canopy of a tree. With this kit we aim to map a tree climber’s movements as they climb. The data then provides a body map showing the skeleton and muscle structure of the climber. We are recording different access and climbing methods in order to analyse the effect they each have on a climber’s body. We then plan to look at tasks in the tree and the work positioning options when undertaking those tasks.

Arborists always complain of suffering from musculoskeletal injuries caused by repetitive stretching and supporting large loads in contorted postures. The prolonged use of these techniques can result in muscle sprains and degenerative joint problems. This project is investigating correlations between working practices and chronic injury rates to provide an evidence basis for the recommendation of safer working practices and improved healthcare for arborists. This in turn, we hope, will enable better training and development of techniques for future generations, prompting a longer working life and reducing the drain on our skilled workforce.

The project set out to establish whether there are significant differences between arborists trained in traditional doubled or moving rope technique (MRT), improved friction management MRT and modern developing stationary rope techniques (SRT). Climbing tasks to be investigated include but are not limited to: access against the stem, free hanging rope access, movement in the canopy to a pruning target, pruning cuts with a saw and descent from the tree. We hope to look at chainsaw work in time.

Coventry University’s Biomechanics Group has experience of applying motion-capture methods across a broad spectrum of applications from sports performance optimisation through product design to medical device analysis. The Biomechanics Group has developed software which is capable of analysing human motion and calculating the forces and torques developed within a person’s body during a diverse range of activities. Using it, correlations will be calculated between loads that occur at major joints within arborists’ bodies and the rate of musculoskeletal injuries.

To support this work with biomechanics, we are using online survey data from working arborists to ascertain their current working methods, the injuries they have suffered and whether they have made any changes to their working practices to reduce the chance of compounding injuries or problems. So far all the evidence has been anecdotal and we hope to gain some meaningful data to better understand the current problem and tree-worker climate.

In summer 2018 we scheduled two days of testing with Barbara May and James Shippen from Coventry University, along with a climbing team. The first morning was spent testing the data-capture equipment: setting it up to ensure it did not compromise the climber’s ability to move freely or the functional and safe use of the climbing equipment. The afternoon was then spent in bench-marking climbing ascent methods and techniques to start building up a dataset to study. That evening we all met to plan for the following day: we had proved the concept worked well and could see the results on screen. On day two we expanded the datasets and looked at movement in the crown while branch walking.

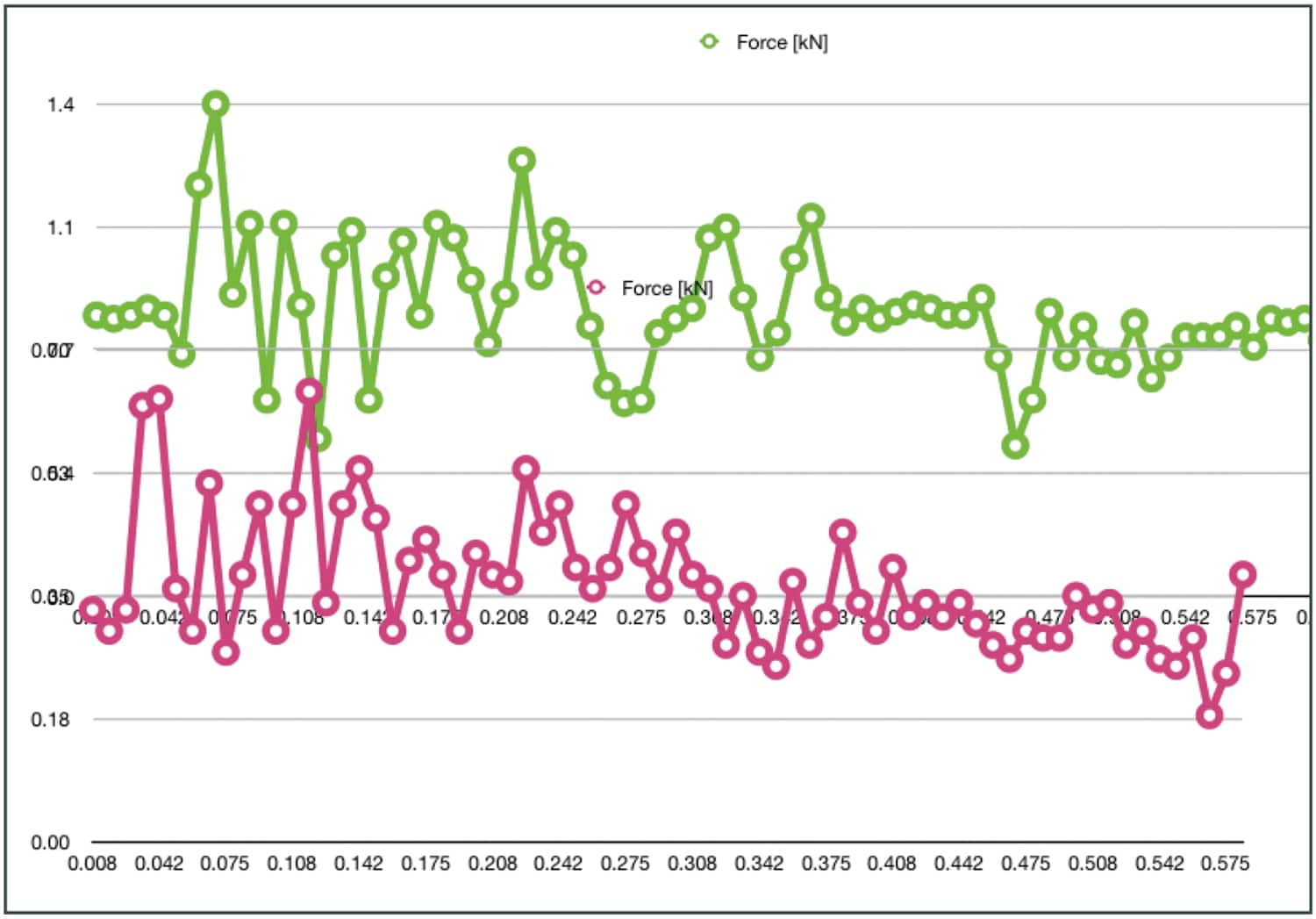

Graph 1: Loads on an arborist’s climbing line measured in kN while branch walking using SRT (green) and MRT (red).

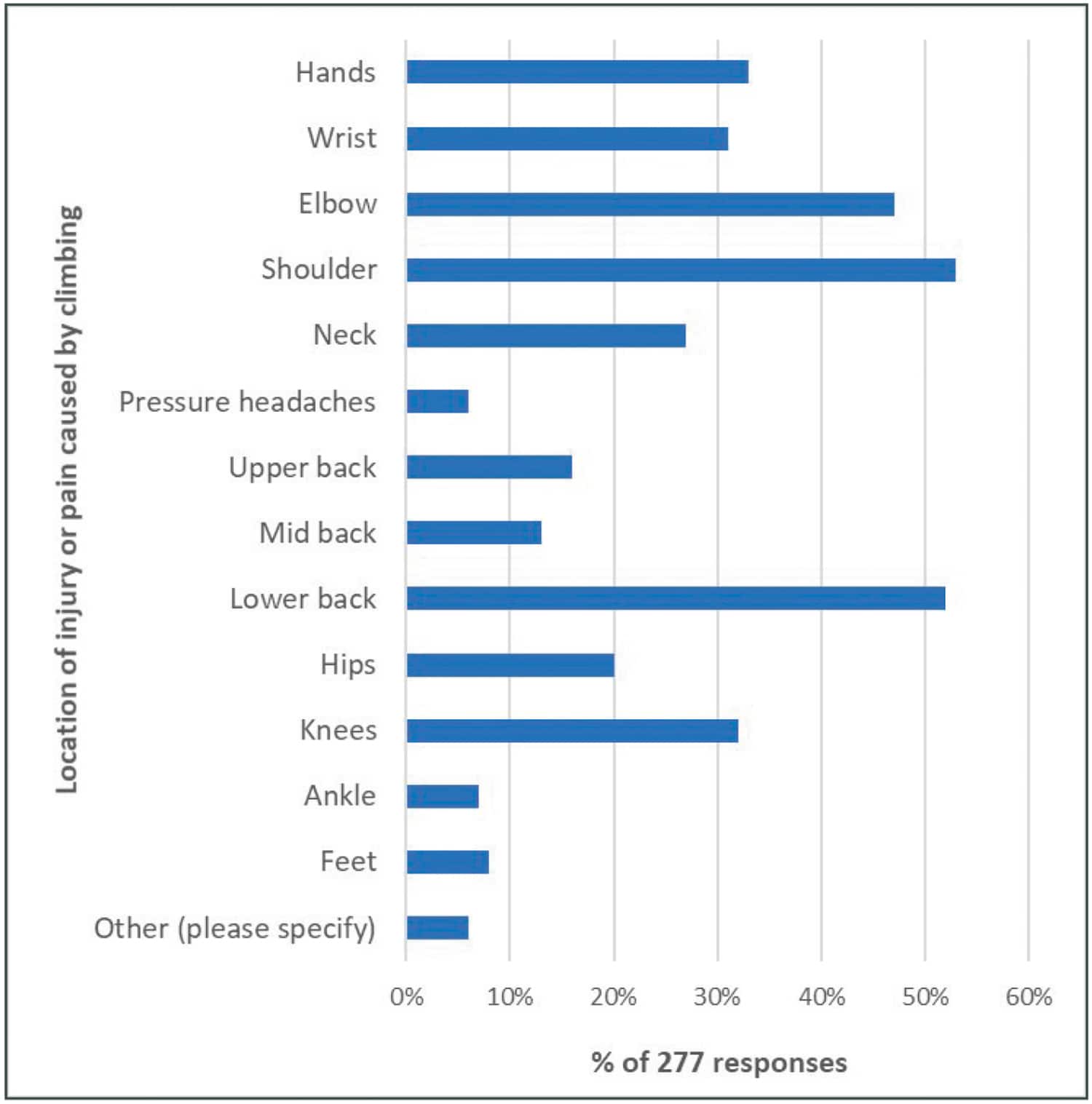

Graph 2: Where did it hurt? Reported sites of injury and pain caused by climbing activities; data from 277 respondents.

Graph 1 shows the loads on the climbing line for SRT in green and MRT in red. We captured this data for all methods tested. In analysis we found we had one big issue. Up until this point the software and hardware have been used to study people who are in contact with the ground. A tree climber moving up a rope has their weight in the rope, harness, hands and feet, and passing contact with the tree.

Tracking these transferred loads to give a full and accurate picture of the muscle loading and torques in the joints is a major hurdle we need to overcome. However, from the captured datasets we can now model the methods and compare these using nominal loads. This part of the work will rely on the observation and experience of a climber to inform us where the connected load distributions are felt in the body whilst moving around the system. This will demonstrate the theory but will not give us full reportable science, just anecdotal interpretation.

Measuring load.

We also ran an online survey asking key questions of people in the tree-care industry. With over 325 responses and a good broad dataset, we have made some clear discoveries. The main conclusion we can draw is that tree climbers do indeed suffer from muscular and skeletal injuries, but there are also patterns of common areas where people get injured.

We asked ‘Have you ever suffered any muscular or skeletal injuries or pain caused by climbing activities?’ Of the 315 people who answered the question, 273 (86.67%) said yes. Those who answered yes were then asked to specify where the injuries or pain occurred. The results from the 277 who replied appear in Graph 2. No data was gathered as to the extent of the pain or injuries caused, nor information relating to the duration of work, nor background on previously carried injuries and so on; we may try a follow-up survey to see if we can dig deeper into these issues.

In May three of the research team were invited to present a work-in-progress session at the German Tree Care Conference Climbers’ Forum in the town of Augsburg. In this 90-minute session we walked the audience through the results of the survey, explained what biomechanics are and how the science has developed, and outlined how the new technology we are using actually works. We then did a live demo of data capture where the audience could see the movements. I also demoed climbing in MRT and SRT on a tower as a three-dimensional model on the screen. We showed some of the data captured with the muscles laid on to the model and the effects of torques using estimated loads from our load cell data. I also attended the ISA’s conference in August at Knoxville to present a condensed 60-minute talk similar to that given in Germany but without the live demo of the technology.

Testing with biometrics experts from Coventry University and a climbing team.

Work on quantifying the unknown key loads on a climber’s hands, feet and harness is ongoing. The load cells currently available for this project, even though designed for rope load measurements, are just too big to add in to a harness system without changing the climbing system’s ergonomics to the point of removing the real moments and therefore affecting the true picture. To this end I am working on installing small strain gauges to items of climbing equipment and developing small microprocessors to capture the data. Once we have some working prototypes of these instruments, we can work on software to sync the data to motion-capture data in Mat Lab to give us a fuller picture. From there we can then look at new complete datasets of the hot-spot areas where we have identified the greatest risks to the climbers as a result of certain movements or techniques.

Work on quantifying the unknown key loads on a climber’s hands, feet and harness is ongoing.