Tree planting has been higher than ever on the public and political agenda recently, with many commitments and policy drivers focusing on the subject over the last few months.

Tree planting has been higher than ever on the public and political agenda recently, with many commitments and policy drivers focusing on the subject over the last few months.

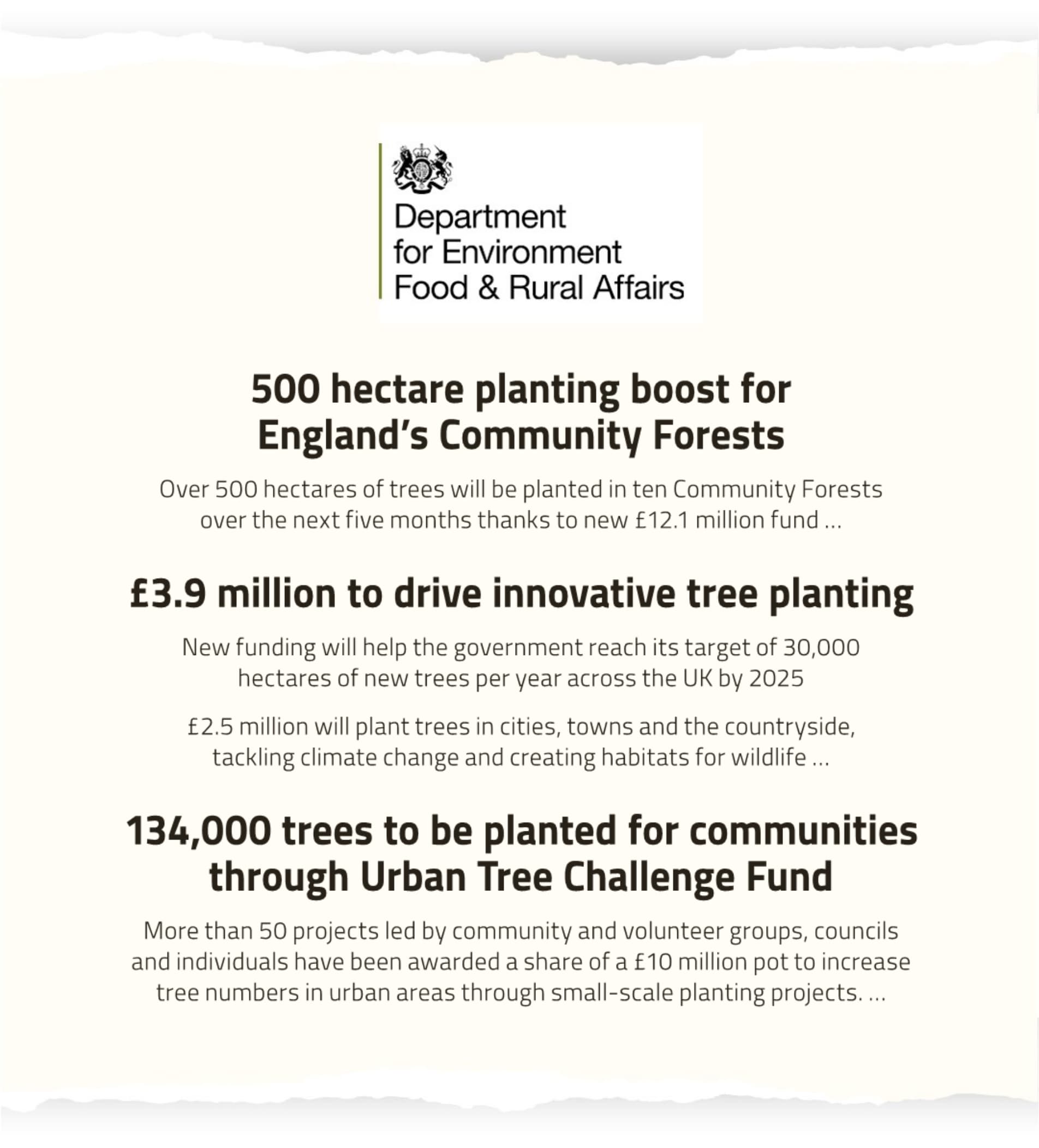

In November and December alone, Defra made three announcements about funding for tree planting: £3.9 million to drive innovative tree planting, a 500-hectare boost for England’s community forests and 134,000 trees to be planted through the Urban Tree Challenge Fund.

This is all good news, of course, and the Association welcomes commitments from government to increasing tree cover. However, we continue to strongly push the message that mass tree planting targets alone are not the answer, and in many cases might not be appropriate at all. Tree establishment is as important as tree planting – there is little value in planting millions of trees if they are left to die. Focusing exclusively on native trees, as some projects do, is unhelpful in urban areas where species diversity is critical if we are to maximise ecosystem services and future-proof our urban forests against climate change and pests and diseases.

In some cases, natural regeneration will be a better option than planting, and the importance of open-grown trees must not be overlooked. We have stressed to government that forestry and woodland management are not the same disciplines as arboriculture and, crucially, if we want these millions of trees to survive into maturity then professional arboriculturists need to be involved at every step of the process, from production, supply and planting through to aftercare and long-term maintenance and management.

The Association has made these points in far greater detail in a series of consultation responses to government documents such as the England Tree Strategy, the Planning White Paper and the EFRA Tree Planting Inquiry, and we are currently working on preparing other consultation responses for later proposals. As you will read in the following sections, we have been lobbying parliamentarians and speaking to members of the House of Commons and House of Lords to make the case that mass tree planting is not always the answer. We also have some great advocates in government, as you can see in the excerpt opposite from the House of Commons debate on the National Tree Strategy.

In addition, we have been making the case for tree establishment, not just tree planting, to the general public through media campaigns and initiatives such as Tree Care Supporter. We will continue to make the case, on behalf of our members and the whole industry, that the right tree in the right place is obviously important, but we also need the right professionals with the right resources.

On Wednesday 16 December the House of Commons sat to debate the National Tree Strategy.

The Association has for the past few years been working on lobbying government to recognise the importance of arboriculture and to utilise the professional expertise of our industry.

Although much of the discussion in the House of Commons debate was centred around large-scale woodland and forestry planting, it was encouraging to see many MPs taking note of the importance of arboriculture and urban trees.

Derek Twigg, the MP for Halton, was a particularly keen advocate for our industry and the need to focus not just on tree planting but on establishment too. In the debate he also quoted from a briefing note which the Association had sent to the All-Party Parliamentary Gardening and Horticulture Group (APGHG). The Association has been an active member of the APGHG for a number of years. Quotations from the briefing note appear in italic.

Mr Twigg said,

‘Promoting tree establishment is very important.

‘“The right trees need to be planted in the right place to maximise the long-term environmental, social and economic benefits of urban trees, as well as ensure that they do not perish and can survive. This means that species are identified, sourced, and planted in the environment best suited to their needs in order that they may flourish. The planting of the tree is a crucial part of the process, but it is but one part: tree establishment is equally as important. In particular, young tree maintenance is essential to enabling a newly planted tree to establish and thrive.”

‘How often do we see that newly planted trees are struggling because they have been through drought or have not been watered properly?

‘“Tree officers, for example, are the custodians of our urban trees, but years of under investment in public sector tree management have left many of them struggling.”

‘Of course, some local authorities do not have tree management officers to speak of.

‘“Trees planted in urban settings need maintenance which has not always happened in the past, as responsibility is often passed between local government departments. Ensuring that local governments have the capabilities to maintain trees in the long term is crucial to ensuring that planting efforts are not wasted. The right professionals with the right resources are needed, but under-investment in the industry in recent years has left many struggling.”’

You can watch the debate in full here: parliamentlive.tv/event/index/5ab218b1-c48b-4227-bfab9cc6902e3ca8?in=09:30:00#player-tabs.

You can also see the transcript here: hansard. parliament.uk/Commons/2020-12-16/debates/47645D5B-2DA0-49938AE3-61995025D3D4/details.

The question as to whether or not the targets are sufficiently ambitions and realistic presupposes the answer to an equally important question – are the targets desirable? The quantities of trees being promised essentially amounts to new plantations. It is not always appropriate to seek the greatest number of new trees in any given space. Open-grown trees are one of the most important habitats there is, not to mention their value in carbon sequestration. Many of our most important ancient and veteran trees are in fact open grown specimens. It may well be possible to plant ten thousand trees in an area the size of a football pitch but is it desirable to do so where perhaps only half a dozen would be more appropriate for the long term? When dealing with trees it is important to think in tree time, which does not confine itself to the political cycle or human scale. If there are to be mass tree planting targets then they need to be strategic and joined-up rather than just a series of escalating numbers.

Using the term ‘tree planting’ to cover woodland creation, forestry plantations and the expansion of urban forest is unhelpful in the extreme. For woodland creation it may be more appropriate, cost effective and environmentally sustainable to use natural regeneration rather than mass tree planting. It may be most appropriate to focus planting efforts on whips, perhaps prioritising native species. In an urban area this approach is unlikely to work. The perceived, and often mistaken, distinction between native and non-native should be disregarded; a diverse urban forest is essential in order to mitigate the risk posed by pests and diseases and climate change and to maximise the benefits the urban forest can deliver. In parts of the world such as Florida or Papua, where there are hundreds of native trees to choose from, it might be appropriate to confine species selection to native trees. In the UK, where there are no more than 40 native trees and few of them suitable for selection as a large-canopy urban species, it would make no sense whatsoever.

In urban areas it is typically necessary to plant trees at a size far larger than whips. Under current circumstances these will n all likelihood be imported into the UK at some stage of their life rather than being UK-grown – this is absolutely fine as long as strict biosecurity measures, perhaps involving an appropriate period of quarantine, are observed. If the ultimate aim is to move towards an increase in the proportion of urban trees which have been grown in the UK then there must be a significant investment into the nursery industry to enable them to expand their production and grow more trees from seed. This will require guarantees on the part of the public sector that these trees will be purchased and planted when available. The timescale to produce a 12–14cm tree for planting in an urban area is a minimum of five years, and the larger the tree required, the longer the process takes.

When undertaking new tree planting projects, it is vital to consider green equity and to do everything possible to ensure equal access to trees and green space for all. Green equity can be defined as fair access to, and governance of, urban forests regardless of differentiating factors such as socioeconomic status, racialization, cultural background or age (see Nesbitt, L. et al (2018) The dimensions of urban green equity: A framework for analysis. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, V34). Simply put – we know that trees bring benefits, but are those benefits being enjoyed by all? It is also important to note that the answer to improving green equity issues is not simply to increase tree planting in more deprived areas; there are more complex factors around structural representation and community engagement etc. which must also be addressed.

The recent trend for mass tree planting and ever-escalating targets masks the reality that the act of putting a tree in the ground is only one small part of a decades-, or even centuries-long, process which includes nursery production, planting specifications, young tree maintenance, inspections and long-term tree care. We must ensure that trees are established rather than just planted; there is little value in spending millions of pounds in planting trees which never make it to maturity. And at every stage of the lifecycle of a tree in an urban area there should be appropriate involvement from the relevant arboricultural professional. And, like purchasing, planting and establishing a new tree itself, the funding required to properly train and support these professionals should be seen as an investment, not a cost.

The concept of ‘right tree, right place’ still stands, although it is often overused and frequently misunderstood, with some failing to appreciate the importance of professional arboriculturists in deciding what is the right tree and where is the right place. The drive for mass planting – an inevitable consequence of ever-escalating tree planting targets – risks ignoring the nuances of location, species, provenance, quality, establishment and long-term maintenance etc. and focuses only on the numbers going into the ground.

It is encouraging that in recent years the profile of trees has increased so much in the political and public mind. However, arboricultural professionals are still not recognised as being essential to the success of the urban forest. Arboriculture remains an unregulated industry and it is still possible for anyone in the UK to purchase a chainsaw and immediately call themselves an arborist. This is detrimental not only to the reputation and confidence of the profession, but to the health of the urban forest as a whole. The England Tree Strategy makes the observation that there is a workforce and skills shortage in forestry; for the future of the urban forest it must be recognised that the same problem is faced by the arboricultural industry as well.

All parts of the arboricultural industry are important in protecting and managing existing trees, but the role of the Local Authority tree officers – the custodians of the urban forest – is particularly crucial. The Planning White Paper correctly identifies the need for Local Authorities to have the right people with the right skills, and it is a positive step to see acknowledgement from government of the detrimental impact of budget cuts in recent years. If the proposed policy framework relating to trees – including the Planning White Paper and the England Tree Strategy – is to be successfully implemented, then appropriately qualified and properly resourced tree officers should be employed by every Local Authority in the country, without exception. A healthy population of urban trees requires a healthy population of urban tree officers, and any administration which claims to care for trees must acknowledge the importance of the professionals who care for those trees.

This article was taken from Issue 192 Spring 2021 of the ARB Magazine, which is available to view free to members by simply logging in to the website and viewing your profile area.